The Broadhead-Bell-Morton Mansion at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue, NW

Updated: March 28, 2025

The mansion at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue has been home to famed inventor Alexander Graham Bell, U.S. vice president Levi Morton, and the Russian embassy. For the past 75 years, it was home to the headquarters of the American Coatings Association.

The original Victorian era, Queen Anne-style house was built in 1879 for John Thornton Brodhead, a West Point graduate and Marine Lieutenant, and his wife, Jessie. It was designed by prominent Philadelphia architect John Fraser, who had designed the British Legation building at Connecticut Avenue and N Streets in 1873, Senator Van Wyck’s house at 1800 Massachusetts Avenue Northwest, and the still-standing James Blaine mansion at 2000 Massachusetts Avenue, NW.

The Brodheads may never have lived in the house themselves. In 1879, they were living in a more modest townhouse on 14th Street. In 1880, Brodhead resigned his military commission and a year later was living in Detroit where he had set himself up in the real estate business. The house was therefore probably built on speculation by the not-so-wealthy Brodhead, hoping to take advantage of the boom in development and the sudden demand for large homes in the Dupont Circle area.

In 1882, Brodhead sold the house to Gardiner Green Hubbard, the father-in-law of Alexander Graham Bell, founder and president of the Bell Telephone Company, as well as later the founder of the National Geographic Society. Not long after Bell Telephone was launched, Hubbard realized that he needed Bell—who served as his chief electrician—close by, and his daughter Mabel even closer, and used the Brodhead house to lure them from Boston to D.C.

Once in their new house in D.C., Bell installed the city’s first electric burglar alarm system with an elaborate system of wires and bells that connected every door and window in the house to a room he referred to as the “central office.” Indicators in the central office would show instantly whenever a door was opened or shut, or only partially opened. If anyone tried to enter the house at night, bells would sound.

The original Brodhead house was not large enough for Bell and he added a two-story addition on the northeast corner, and then a third floor with a steep slated roof. In 1887, a fire destroyed much of the building. Although the damage was more extensive than what the insurance policy covered, Bell had the mansion restored.

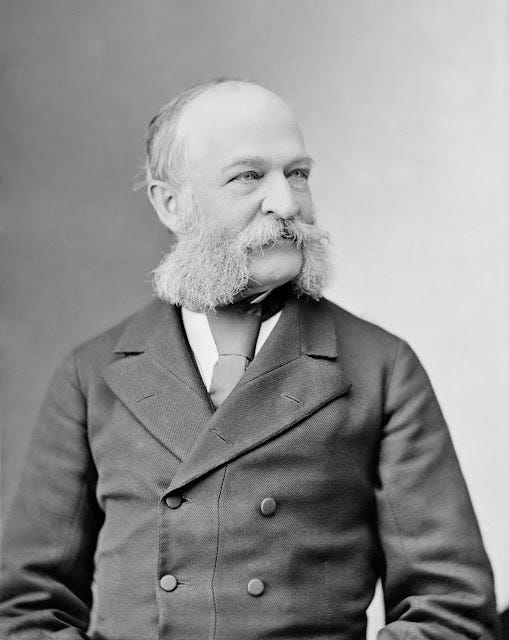

Only two years after the fire, Alexander Graham Bell sold the house for $95,000 to Levi Parsons Morton just prior to Morton’s swearing in as vice president under Benjamin Harrison. Bell and his cousin, Charles Bell, who had married Mabel Bell’s sister, then both built houses next to each other and just across the street from their father-in-law Hubbard. Alexander built at 1331 and Charles at 1325 Connecticut Avenue.

Only two months after purchasing the house, Morton brought back the house’s original architect, John Fraser, to add a new dining room. Morton lived at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue until the end of his single term in office 1893. He then leased the property to a series of tenants including Massachusetts Congressman Charles Franklin Sprague, and Count Arturo Cassini, the Russian Ambassador to the U.S.

Count Cassini occupied the house with his teenage daughter Marguerite, whom he passed off as his grand-niece and adopted daughter, and a governess, who was secretly Cassini's wife and mother of his daughter.

Marguerite disliked the building the Russian government had rented on I Street. She considered the Morton mansion a dream home and upon learning that the house was vacant, single-handedly orchestrated the lease of the mansion from Morton. It served as the Russian embassy between 1903 and 1907.

Marguerite Cassini’s love affair with the house was undoubtedly short-lived. Bell’s alarm system was still operational, causing her no end of grief as it allowed her father to know when she was sneaking in and out of the house, often forcing her to crawl out a second story window to go undetected.

After leaving Washington, Morton went on to serve briefly as Governor of New York and was instrumental in creating Greater New York City, merging Brooklyn with New York City. He then made an unsuccessful bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 1896, but lost to William McKinley. After a return to the world of finance, and creating the Morton Trust Company in 1897, Morton decided to retire and in 1912, returned to his home in Washington.

When Morton returned to the city, the neoclassical Beaux-Arts architectural style was all the rage and anyone who was anybody had to have a home in the latest style. Under the hand of architect John Russell Pope, who also designed the Hitt mansion at 1511 New Hampshire Avenue, and later the Jefferson Memorial and the West Building of the National Gallery of Art.

Under Pope’s hand, the house was transformed into its present-day form. Pope removed the Victorian-era rounded bays, as well as Bell’s Mansard roof and encapsulated what was left of the old house in a new limestone shell to create the more proportionally balanced and classical look typical of the grand mansions being constructed in the nearby Dupont Circle neighborhood at that time.

Morton lived in the house until about the time of his death in 1920. It then went on to serve as the home of the National Democratic Club until 1940, when it was sold to the National Paint, Varnish and Lacquer Association, the precursor to the present-day American Coatings Association. The mansion is now the Embassy of Hungary