William Tunnicliff's Washington City Hotel and the Old Brick Capitol

In May of 1799, William Tunnicliff announced that his large and commodious new hotel near the Capitol, the Washington City Hotel (often referred to as just “Tunnicliff’s”), was complete and ready for guests. This building stood on lots on First Street and what was then the 100 block of A Street, NE, now the site of the Supreme Court.

The three-story Washington City Hotel was built of red brick, with the front on A Street ornamented with molded free stone from the same quarries that supplied the material used for the White House and the older parts of the Capitol. It also had extensive stabling in the rear to accommodate coaches and teams arriving daily from Baltimore.

During a visit to Washington in the summer of 1800 and before the unfinished White House was inhabitable, President Adams stayed at Tunnicliff’s new Washington City Hotel. Later that year, Secretary of State John Marshall, shortly to become 4th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, lived at the hotel as well.

In August 1804, Tunnicliff’s wife passed away and only a few days later, he and his partner George Walker sold the Washington City Hotel to Pontius Stelle. At this point in time, Tunnicliff drops out of the hotel business. Stelle had arrived in Washington in 1799 from Trenton, New Jersey and upon his arrival established a small boarding house on New Jersey Avenue.

Stelle was no sooner settled in Tunnicliff’s hotel, for which he had only paid for in part, when his sites fell upon a new hotel building that was part of the splendid new set of row houses on the adjoining square to the south that Capitol Hill proprietor and developer Daniel Carroll was building to become known as Carroll's Row. Stelle leased Carroll’s Hotel—the large end building on the north— in 1805 and established “Stelle's Hotel and City Tavern,'' known as simply Stelle’s for short. He then started advertising to rent out his old hotel on A Street, but it would stand vacant for the next 5 years.

Stelle had a reputation as an hotelier. His hotels were of the highest order in accommodations and class of guests, and were run on the most extravagant scale, with no expense spared to make them models of comfort and luxury according to the fashions and limitations of the day. Yet, he would often not accept payment from many of his favorite guests, preferring their company to paying their hotel bill, which undoubtedly contributed to his financial failure in the hotel business.

Stelle’s Hotel and City Tavern lasted only four years in Carroll's Row. In 1809. Robert Long took over Carroll’s hotel building, but gave up the lease after only one year. Known as Long’s Hotel, it was the site of many festive occasions, including President Madison's 1809 inaugural ball, also attended by ex-President Thomas Jefferson and all the foreign ministers to Washington. The ball was described as the “the most brilliant and crowded ever known in Washington.” An attendee described the guests as a "moving mass" that crowded into the ballroom and broke an upper window sash for ventilation when the air became oppressive.

Five years had passed and Stelle was still trying to unload the old Tunnicliff hotel. In 1810, he put it up for sale and in a newspaper advertisement described its location as prime: “The house fronts on A Street and Maryland Avenue, being the avenue which leads from the Baltimore road and by the Capitol to the Washington Bridge.”

In 1811, Stelle finally found a buyer for Tunnicliff's. Unfortunately, due to a mortgage complication his attempt to sell the building ended up in a law suit with the buyer. The court found in the buyer’s favor, but Stelle was finally free of the hotel. At this point, Stelle was finished with the hotel business and accepted a position in the office of the Comptroller of Currency in the Treasury Department, a position he held up to the time of his death in 1826.

In August 1814, when British forces invaded Washington, the United States Capitol building was burned. Suddenly in need of temporary quarters, the Capitol Hotel Company, a stock company founded by local citizens concerned that the government would leave Washington, was established to erect a temporary building to assure that it stayed. Daniel Carroll, who still owned the vacant lot next to Tunnicliff's on the corner of 1st and A Streets NE, exchanged it for stock in the company. The owners of Tunnicliff''s also bought stock in the company. The Capitol Hotel Company then erected a brick building on Carroll’s empty lot, annexing Tunnicliff's on the adjacent lot as a wing to the new building. Congress would occupy the building from 1814 until 1819, while the original U.S. Capitol Building was being rebuilt.

When the temporary brick capitol was complete, the proprietor of old Tunnicliff’s hotel, John McLeod, opened a hotel near the ruins of what was Tomlinson’s Hotel, which had the distinction of being one of the few pieces of private property burned by the British.

The building acquired the name “Old Brick Capitol “ in 1819 when Congress and the Supreme Court returned to the restored U.S. Capitol Building. Until the time of the Civil War, it was used as a private school, then as a boarding house. John C. Calhoun, former Vice President of the United States, died in the boarding house in 1850.

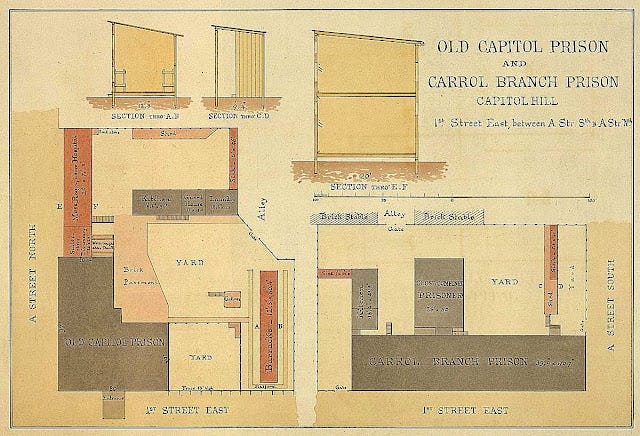

With the start of the Civil War in 1861, the Union Army purchased the building for use as a prison for captured Confederates, as well as political prisoners, Union officers convicted of insubordination, and local prostitutes. Famous inmates of the prison included Rose Greenhow, Belle Boyd, John Mosby, and Henry Wirz, who was hanged in the yard of the prison. Carroll's Row also served as a prison, housing political prisoners. The entire circumference of the ground floor of the Capitol Prison was white-washed to increase the visibility of prisoners attempting an escape.

The government sold the Old Capitol Prison in 1867 to George T. Brown, then sergeant-at-arms of the U.S. Senate. Brown converted the old capitol building into three townhouses that became known as “Trumbull's Row." What was once Tunnicliff’s hotel was rebuilt as the ell to the end house.

Carroll Row was razed in 1887 for the Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress. In 1932, what remained of the old brick Capitol and Tunnicliff’s hotel was razed to make way for the Supreme Court building.

See also:

The Virtual Archaeology of Three Washington D.C. War of 1812 Sites. Author lecture at The United States Capitol Historical Society (USCHS)

--------

Copyright Notice: This article was originally published in The InTowner Newspaper in its 2015 February and March issues. Copyright © The Intowner Newspaper and Stephen A, Hansen. All Rights Reserved.