Cliffbourne: From Country Estate to Civil War Army Hospital

Cliffbourne was an early 19-century estate that once stood on the west side of present day Cliffbourne Place NW, a one-block stretch between Calvert and Biltmore Streets. Cliffbourne, literally meaning "bordering a cliff," was an appropriate name for this estate. Immediately to the north of John Little's house in the Kalorama Triangle neighborhood, it stretched from Columbia Road westward ending at a steep bluff where it met the Rock Creek valley at 20th Street, NW. Cliffourne was the first house built in Kalorama Triangle and over time would also also give its name to a Civil War hospital, an 1898 subdivision, an apartment building, as well as to the street itself.

Cliffbourne was first documented in 1815 when Dr. William Thornton acquired land for a horse farm in Kalorama Triangle from John Holmead and Thomas Peter that would later be acquired by John Little. The deeds from both Holmead and Peter referenced an existing adjacent property owned by John Holmead and Thomas Pairo on Anthony Holmead's Widow's Mite tract of land.

When Anthony Holmead died in 1802, Widow’s Mite was divided among his wife, Susanna, his sons John and Anthony, and daughters Sarah Speak and Loveday Buchannon. Although Loveday inherited part of Widow's Mite, it would never be in her own name; it would have remained in one of her brother's names until she married, in this case her brother John's name.

In 1805, Loveday married German-born real estate broker Thomas Pairo. Instead of transferring the title to Loveday's inheritance completely to her husband, John Holmead's name remained on the title as well. It is probable that Pairo built the Cliffbourne house sometime around 1805 as a home for himself and his bride. The Pairos ultimately returned to live at Holmead family's Rock Hill house in the Sheridan-Kalorama neighborhood.

Sometime before 1826, Col George Bomford acquired Cliffbourne from the Holmeads. In 1822, he had acquired the title to Joel Barlow's Kalorama estate. Like many proprietors at that time, Bomford became heavily involved in real estate speculation, eventually expanding the Kalorama estate to ninety acres.

Bomford's real estate speculation kept him constantly borrowing against one property to secure another. In 1826, he placed the Cliffbourne property in trust to Richard Smith as collateral in order to secure a loan from the Bank of the United States. By 1837, a financially strapped Bomford had failed to repay the loan, entitling Smith to sell the property to cover Bomford's debts. But Smith did not immediately sell Cliffbourne. The property briefly returned to the Holmead family in 1845 when Smith finally sold it to Charles Hedges James, who had married Mary Ellen Holmead. George Bomford never recovered from his losses, and died of in a modest house on I Street, N.W. in 1848.

In 1846, Charles James sold Cliffbourne to Selah Reeve Hobbie, a former Jacksonian Democrat congressman from New York who also served as First Assistant Postmaster General, most of this time serving under Post Master General Amos Kendall. It may have not been a coincidence that Cliffbourne was only a stone's throw away from Holt House where Amos Kendall was residing. But Hobbie never lived at Cliffbourne himself. Immediately after he purchased the property, he leased it back to Richard Smith who in turn sought high-end tenants for the house.

Another Jacksonian Democrat, Jefferson Davis, briefly lived at Cliffbourne at some point between 1853 and 1857 while serving as the Secretary of War during the Pierce administration. An 1896 Washington Post article ("Homes of Jeff Davis," June 21, 1896) described "Cliffburn" as "a pretty little country place... just out in the suburbs on the line of the the electric road to Chevy Chase. Here is was that the Secretary spent the summer for one season."

Cliffbourne next appears on an 1861 map of Washington, D.C., created by Albert Boschke and surveyed in the 1850s, that shows a large estate immediately to the north of the Little farm belonging to Mrs. S. R. Hobbie. The map shows that the house was approached by a long drive from Columbia Road, running along what would become Biltmore Street, and terminating in a circle at the front of the house.

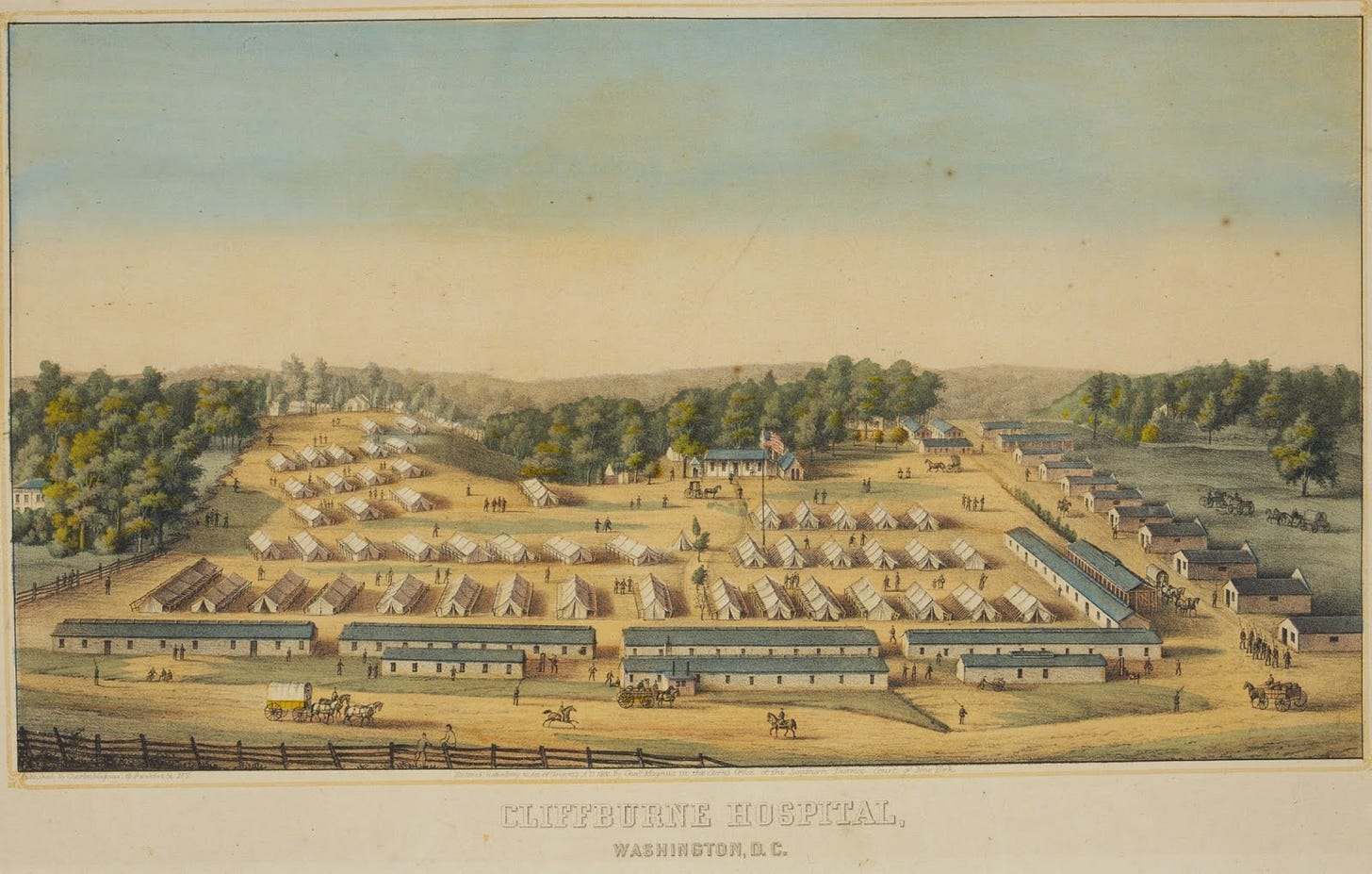

During the Civil War, Ciffbourne was commandeered for use as a United States Army cavalry barracks, when it became known as Cliffburne. The site provided an ideal location for cavalry horses, as it was flat and already clear cut and used as farm and grazing land.

Following the Fifth U.S. Regiment’s departure for the battlefield in 1862, the Cliffburne barracks were converted into the headquarters of the Invalid Corps under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel John Shaw Billings, a surgeon from Cincinnati. When Billings took charge of Cliffburne, he found the buildings and grounds “in an extremely filthy and dilapidated condition,” with no drainage and no water within half a mile. In order to be used as a hospital, additional buildings had to be added, along with 105 hospital tents, to accommodate up to one thousand patients. Either Mrs. Hobbie or perhaps neighbor John Little had been raising and slaughtering cattle on the land at the time, and it was said that “15 hundred loads of offal had to be cleared from the grounds and vicinity of the buildings.”

The Cliffburne hospital was one of the largest and one of the most comfortable in the District. Two wards of the hospital were devoted to Confederate soldiers who were brought in from Williamsburg. Caring for both Union and Confederate soldiers put the hospital in a delicate situation. The older residents of Georgetown and Washington who were sympathetic to the South brought food and drink to the hospital intended for the Confederate soldiers only. Family members of Congress and government officials also brought food, specifying that theirs should go only to the Union soldiers. Billings had to explain that the hospital could not accept gifts under such terms, and they were ultimately left for those who needed them most.

While touring Cliffburne, William A. Bayley, a congressman from New York City, turned to Billings and asked, “You have got a lot of my boys here; I would like to do something for them, something that the papers will notice, you know. What do you think I had better give them?” Billings replied, “They have all got more or less scurvy, and I think fresh strawberries would do them good. You might have a strawberry festival, and have a band here.” Bayley agreed, and the wounded were treated to strawberries and cream. The event was a great success.

Poet Walt Whitman was a frequent visitor to the Cliffburne Hospital, spending many hours and entire nights sitting at the bedsides of soldiers. Whitman himself has often been described as a Civil War nurse, although his actual role was that of a very attentive visitor. In his poem “The Wound Dresser,” Whitman wrote of his experiences in the Washington hospitals:

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all the dark night—some are so young;

Some suffer so much—I recall the experience sweet and sad.

After the army relinquished Cliffbourne, Julianne Hobbie took up residence there. In 1870, in need of more land she purchased thirty-nine acres belonging to Columbia Mills from Charles Francis Adams, the son of John Quincy Adams, as an addition to the farmland she already owned. The small parcel ran along the northern boundary of the land and adjoined the Quaker cemetery. This additional tract of land is now the site of an apartment building at 1836 Adams Mill Road. Julianne Hobbie died in 1898 at the age of ninety-one.

In 1880, Julianne Hobbie sold Cliffbourne to John Bassett Alley, a Massachusetts Republican who had served in Congress from 1859 to 1867. Alley may have also had some prior connection with the Hobbies, as he had served as chairman of the Congressional Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads.

Alley did not hold Cliffbourne for very long. The same year he bought it, in what was basically a property swap, he sold it to Brigadier General Noah L. Jeffries for $20,000. In turn, Alley bought Jeffries's sizeable house on McPherson Square at the corner of Fifteenth and K Streets for $30,000. The transaction may have been pure real estate speculation on Jeffries's part.

In the 1880s, as Washington grew beyond its original planned limits and city streets were being extended, large estates in Washington County were eyed for development. Land owners, trustees, and speculators submitted maps (plats) of proposed subdivisions to the city for approval. [1] Old estate owners would cash in on a higher value for their properties resulting from being broken into smaller, more easily sellable house lots with improvements (water and gas lines) in a new development. Many of the existing large houses were razed as they did not conform to the new subdivision plats. Throughout the development pressures of the 1880s and 90s, the old Cliffbourne house managed to survive.

In 1888, the Cliffbourne estate was purchased by Mrs. Effie Hinckley Ober Kline, who possibly bought the property sight unseen on speculation. Kline was an American opera manager and booking agent who had founded the Boston Ideal Opera Company (later known as "The Bostonians") in 1879. Her husband, Virgil P. Kline, was a personal attorney of John D. Rockefeller and worked for Standard Oil Company for many years before he died in 1917.

Kline entered into a contract to sell Cliffbourne to the real estate firm of Presbrey & Green for $110,000. Presbrey & Green then developed a plat for the subdivision of the land and submitted it to the City Commissioners for approval. The plat left the old Cliffbourne house in place, providing it with its own lots (yellow structure on lots #8 and #9 on the map below). In 1899, the firm confidently placed the new development on the market, assuming that the subdivision would be approved and the sale would go through. The subdivision was denied as Kline, described as "non-resident and absent," never signed off on it.

The same year that Effie Kline contracted to sell Cliffbourne to Presbrey & Green, real estate developer and future Nevada senator from Nevada Francis Griffith Newlands chartered the Rock Creek Railway Company. The charter was for a single track, running from the intersection of Connecticut Avenue and Florida Avenue (then Boundary Street), up Columbia Road, passing through Cliffbourne to Woodley Lane, and then connect on to Woodley Park.

In 1889, Presbrey & Green sued Kline for failing to deliver on the contract to sell Cliffbourne to them for which she had already received $5,000 in advance. She had refused to sign the off on the subdivision plat, the deed, or refund the money she had already received. Kline knew that she could now get a better price for Cliffbourne from Newlands and that the financial gain of holding out for a better price was well worth the costs of any lawsuit. The case was ultimately dismissed.

In 1894, Effie Kline sold Cliffbourne to Newlands for $185,000 — $75,000 more than she was offered by Presbrey & Green only six years before. The next year, Newlands began laying Cincinnati Street (now Calvert Street) running along his Rock Creek Railway tracks.

Throughout both Kline's and Newlands's ownership of the old Cliffbourne house, it continued to serve as a high-end rental property. In 1890, it was occupied by Senator Lyman Rufus Casey of North Dakota, but his duties as Senator made it necessary for him to move closer to the Capitol. The following year, it became home to its last resident, Marvin Chester Stone—the inventor of the paper bendy drinking straw, or “artificial straw.”[2]

In 1898, Newlands submitted a subdivision plat for Cliffbourne. The plat only subdivided the land to the east of the old house, leaving the land the house and land occupied by Marvin Stone in place for the time being on a single, large lot (Lot #3 below). The same year, Newlands put the Cliffbourne subdivision on the market with Cliffbourne still standing.

Marvin Stone died in the Cliffbourne house on May 17, 1899 following a lengthy illness. Immediately following Stones' death, Cliffbourne was razed and and its large lot subdivided. The year it was razed, the site was replaced with two Craftsman-style houses at 2504 and 2506 Cliffbourne Place NW designed by architects Marshall and Hornblower, and a three-story rowhouse at 2508 Cliffbourne Place. The rest of the land was quickly developed in the following years.

End Notes:

1. See "A Catalogue of Suburban Subdivisions of the District of Columbia, 1854-1902." Matthew B. Gilmore and Michael R. Harrison. Washington History, Vol. 14, Number 2, Fall/Winter 2002.

2. For a more in depth look into Marvin Chester Stone's “artificial straw,” see Matthew B. Gilmore's July 15, 2015 article "What Once Was: Washington DC, Center of Manufacturing" on his Washington DC History Resources blog.

This article was adapted from the author's book Kalorama Triangle: The History of a Capital Neighborhood.