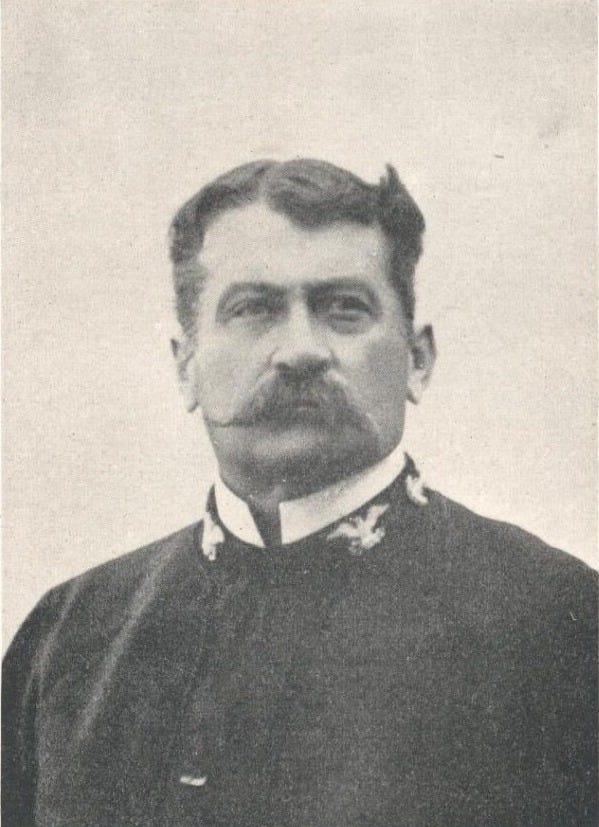

William Hemsley Emory Jr.

The Rescuer of the Greely Expedition

The year 1879 saw the arrival of another new significant military resident to Washington, William Hemsley Emory Jr. Unlike the members of the military set who had followed their Republican generals to Washington after the Civil War, Emory was young and had not served in the war, having only graduated from the Naval Academy in 1866 at the age of twenty.

While Emory hailed from the old Washington “Cave Dwellers”— wealthy southern Democrat families that were in Washington from its founding—he was also part of a new wave of socialites who would transform the city’s Dupont Circle neighborhood in the 1880s—those with money, and a lot of it.

In 1879, the thirty-three-year-old Emory, then a navy lieutenant, contracted the architectural firm of Smithmeyer and Peltz (which later would design the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building) to design a house for him, his wife and their daughters across the street from the British Legation at the intersection of Connecticut Avenue and Nineteenth Street at 1301 Connecticut Avenue NW. But due to the demands of his naval career, he and his family lived there for only short periods of time between assignments until Emory finally retired as a rear admiral in 1909.

One of Emory’s more noteworthy assignments during his naval career was commanding the USS Bear, one of three rescue ships sent in search of the survivors of the Greely Expedition. The Greely Expedition had set out to the Arctic in 1881 to collect scientific information in the Lady Franklin Bay region and became stranded, cut off from food and supplies. On June 22, 1884, less than two months after his departure, Emory sighted the survivors of the expedition, who for months had been existing on moss, leather sledding equipment and whatever small game they could find. By the time they were discovered, most had died or gone mad from deprivation. The six that survived resembled skeletons. The surgeon accompanying the expedition had committed suicide. Greely died before he could be returned to the States.

During most of his active career, Emory was stationed away from Washington and leased out the house on Connecticut Avenue. At one point, he rented it to Representative John Glover of Missouri, who would later marry Augusta Patten, one of the Patten sisters who dominated society from their home on Massachusetts Avenue. He then rented the house to naval colleague and friend Lieutenant Richardson Clover, who would later build his own house on New Hampshire Avenue.

In 1908, after several years of absence, Mrs. Emory returned to Washington while her husband was in command of the USS California. The following year, William Emory retired with the rank of Rear Admiral and joined his family at his home on Connecticut Avenue. They spent the summer seasons at their home in Roslyn on Long Island that adjoined the Whitney estate.

One of Emory’s daughters, Blanche, did not look too far nor too long for a husband. Within a year of the family’s return to Washington, she met and married Esmond Ovey, a third secretary at the British Legation just across the street. Ovey had only arrived in Washington from Paris the year before they married.

The ceremony was held in the house and attended by only a small company of family relatives, the British ambassador and his wife and members of the British Embassy staff and their families. The reception and breakfast that followed included Washington’s diplomatic core, as well as many Dupont Circle neighbors. The month they were married, Ovey was promoted to second secretary and later went on to become one of Britain’s outstanding diplomats, serving as ambassador to Mexico, Brazil, the Soviet Union, Belgium and Argentina.

After the marriage of Blanche to Esmond Ovey, the Emorys left the Connecticut Avenue house, leasing it to Mrs. John Jackson, who was also hosting the Swedish Legation there. Proximity again proved key in a marriage to the diplomatic core in Washington. Mrs. Jackson’s daughter, Laura Wolcott Jackson, married August Ekengren, the Swedish secretary and counsellor who would later become the Swedish minister, who was living in the house at the time.

The southern part of Connecticut Avenue at this time was quickly becoming known as the “foreign quarter,” with the Swedish Legation taking possession of the Emory house, the British Embassy just across the street and the Austro-Hungarian Legation at 1305 Connecticut Avenue in the former home of Senator David Levy Yulee.

Hoping to capitalize on the commercial expansion making its way slowly north along Connecticut Avenue, Emory attempted to sell his house in 1912 to a developer who planned to remodel it into stores and offices, but the deal fell through. Mrs. Jackson remained in the house until 1916, when it was demolished in order to erect the seven-story flatiron building that stands on the site today. Part of the new building became home to the D.C. Chapter of the American Red Cross where many Dupont Circle women volunteered for the war effort.