Anything Goes: The Life and Times of Evalyn Walsh McLean

“When Mrs. Ned McLean (God bless her) can get Russian reds to “yes” her, Then I suppose, anything goes " Cole Porter

"There are many other great houses in the Capital, which by sad changes have been resolved into dust-stained mysteries. I have been in all of them: when they were alive, gay with music, laughter, champagne—when they were bright with jewels, fine fabrics, and lustrous eyes."

From Evalyn Walsh McLean's 1936 autobiography Father Struck It Rich.

In 1903, Thomas Francis Walsh, often referred to as the “Colorado Monte Cristo,” who had emigrated penniless from Ireland in 1869 at the age of nineteen, completed building the most expensive private house at the time in Washington, at the cost of $835,000.

After losing his first fortune in the Panic of 1893, Walsh made a second fortune by discovering and opening the Camp Bird gold mine in Ouary, Colorado. At its peak, the mine was producing $5,000 worth of gold per day. Walsh sold the mine in 1903 for $5 million and decided to plant roots in Washington.

When Thomas Walsh arrived in Washington in 1898 with his wife, Carrie, his son Vinson, and daughter Evalyn, he first purchased a house at 1825 Phelps Place in Washington’s Sheridan-Kalorama neighborhood. Walsh did not know what exactly would be required to properly set up a home with all the necessary accoutrements required of his new status, so he bought the house completely furnished with all the books, ornaments, rugs, curtains, towels and other intimate appurtenances of the “cultured.”

It was in this house that Walsh’s daughter, Evalyn, was introduced to friends Alice Roosevelt and the Russian ambassador's daughter, Marguerite Cassini. Evalyn was shocked at a party in the house to see Alice offer a cigarette to Marguerite Cassini, something very taboo in 1901. The house still stands and is now the Russian Cultural Center.

In 1901, Walsh hired New York architect Henry Anderson who designed the massive four-story, sixty-room mansion at 2020 Massachusetts Avenue. The mansion featured a unique façade of combined Renaissance, Baroque and Louis XVI architectural elements, within an overall Art Nouveau context. The Walshes referred to the house simply by its street number, 2020 (“Twenty-Twenty”).

The interior of the house was just as spectacular as its exterior. Walsh wanted a main staircase reminiscent of an ocean liner, so Anderson created an open-decked promenade of carved mahogany through three floors of the house. He placed a ballroom with a pipe organ on the top floor of the house and installed a rope-pulled elevator to reach it. But the elevator only held four people at a time, and the Walshes would often invite four hundred guests to their balls. It could take up to an hour and a half for all the guests to reach the ballroom. An apartment was created in the house for family friend, King Leopold of Belgium, which was later used by his son, King Albert, when he visited Washington. There is also a legend that a slab of gold is built somewhere in the foundation.

One of the Walshes’ dinner parties was said to have cost $200 a plate. The great room in which it was served had been converted into a flower garden, with flowers sent from Florida and fruit from California by special express. An orchestra played operatic selections from behind a lattice of American Beauty roses. Hanging from the ceiling and suspended just over the dining room table was a great flower balloon, lit with electric lights. At the end of the dinner, the balloon swung open and a shower of songbirds greeted the guests with a rhapsody of melody.

In the summer of 1905, while staying in a rented house in Newport, the Walshes’ seventeen-year-old son Vinson was killed when he lost control of an electric car he was driving. Evalyn was also in the car, but survived with a crushed leg from which she would never completely recover. Ironically, Evalyn's brother Vinson had also died in childhood as the result of an automobile accident.

After Thomas Walsh’s death in 1910, Carrie Walsh continued to live and entertain at 2020. In 1919, she converted much of the house into a garment factory, where she and her “war workers” were busy converting used and discarded clothes into clothing for needy European children after the war. The salons of the house were full of tables of garments and chests and boxes of materials. One room was dedicated to sewing machines; another contained knitting machines and turned out sweaters, stockings and mufflers. It was Carrie’s intent that this work would serve as a model for other American cities.

In 1919, Carrie Walsh hosted a dinner given by Vice President and Mrs. Thomas Marshall for Belgian king Albert and Queen Elizabeth. The Marshalls were filling in for the ailing President Wilson, as the White House was no longer a suitable venue for state dinners. The Marshalls, who were close friends with Mrs. Walsh, asked to use her home. Mrs. Walsh was the only person not of official society at dinner, but after dinner, she was decorated by Queen Elizabeth, not as a courtesy for the dinner, but for her work` for the benefit of those in the devastated regions of Belgium, France and Italy during the war.

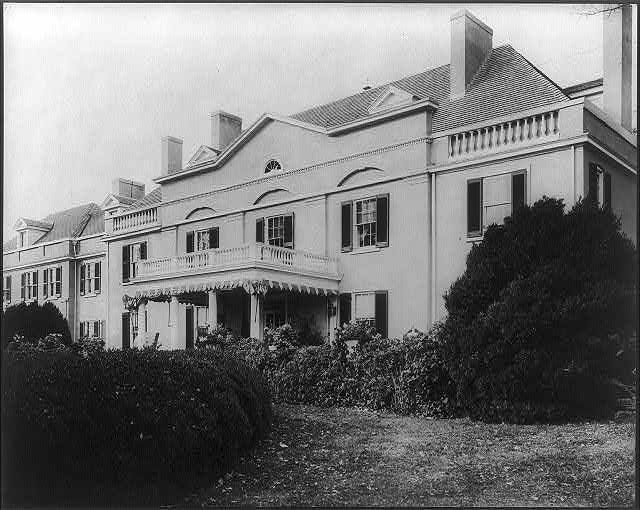

In 1908, Evalyn Walsh married Edward “Ned” Beale McLean. Through his father, Ned was heir to both the Washington Post that John McLean had acquired from Beriah Wilkins in 1905 and the Cincinnati Enquirer publishing fortune. Evalyn’s close friend and confidante Alice Roosevelt never took a liking to Ned and called him a “pathetic man with no chin and no character.” While the McLeans spent some time at 2020, they spent most of their time at Friendship, a sprawling country mansion on Wisconsin Avenue in Washington designed by John Russell Pope for Ned’s father. In addition to the Hitt mansion on New Hampshire Avenue, Pope also designed more than two dozen notable Washington buildings, including the Jefferson Memorial and the National Gallery of Art.

Ned and Evalyn had four children: Vinson Walsh McLean, Edward Beale McLean Jr., John Roll McLean II and Evalyn Washington McLean. Vinson, their first child and named after Evalyn's brother, was popularly known as the “Million Dollar Baby.”

In 1911, Ned McLean paid Pierre Cartier $180,000 (over $4 million in today’s dollars) for the 45.52-carat blue Hope Diamond. Along with it, he also bought another famous diamond, the 94.00-carat Star of the East. The Hope Diamond was supposedly cursed, and many of the events of Evalyn’s life have been attributed to that curse. She was fascinated by the diamond's curse but was not too concerned about it. She wrote in her memoir Father Struck It Rich: “I had it blessed myself and I am sitting back on the sidelines letting the curse and the blessing fight it out together. Personally, I have so much faith in goodness and right working out in the end that it never worries me."

Throughout the rest of Evalyn's life, the Hope Diamond became her emblem. It is hard to find a public photograph of in which she is not wearing it. She was said to keep it in her couch cushions or in her toaster, to wear it swimming, and even to allow her dog to wear it to shock guests. Even when she fell on hard times in the 1930s and the Hope Diamond was in and out of pawnshops, she never lost possession of it.

Evalyn and Ned’s ill-advised and highly publicized trip to Russia shortly after the Russian Revolution in an attempt to get Ned’s uncle George Bakhneteff reinstated as the Russian minister to the United States is memorialized in the famous 1934 Cole Porter musical Anything Goes in the lines:

“When Mrs. Ned McLean (God bless her)

Can get Russian reds to “yes” her,

Then I suppose

Anything goes.”

By 1927, the McLeans’ marriage was on the rocks. Evalyn’s addiction to morphine and Ned’s alcoholism and infidelities led to their eventual separation, and Evalyn filed for divorce in 1929. Evalyn eventually decided against a divorce and had Ned declared insane in 1933. Ned died eight years later in a Baltimore hospital, leaving Evalyn with little money, as they had gone through a fortune of $100 million while in the prime of their lives. Carrie Walsh died in 1932 in the Massachusetts Avenue house.

Along with Evalyn, quite a few Dupont Circle residents lived well into the twentieth century. But times had changed and the days of maintaining a large seasonal house and entertaining lavishly had passed. A series of financial panics, the introduction of income tax, the First World War, the stock market crash of 1929, and the Great Depression all took their tolls and sealed the fate of the lavish lifestyles of the preceding decades in Dupont Circle.

Evalyn and Alice Roosevelt Longworth remained life-long friends. In her book Alice: Alice Roosevelt Longworth, from White House Princess to Washington Power Broker, Stacy Cordery recounts an exchange between the two when Evalyn had fallen upon hard times during the Great Depression. One day, Evalyn arrived on Alice’s doorstep in tears and bearing her new itemized budget. “Alice, what will I do?” she cried, “I simply can’t get my budget below $250,000 a year. Flowers, $40,000; household, $100,000; travel, $35,000…” Past her initial shock and not wishing to upset her friend further, Alice simply replied, “You are quite right. You simply can’t shave it one cent.”

Upon the death of her mother in 1932, Evalyn inherited the Walsh mansion at 2020 Massachusetts Avenue. But she left the house vacant, preferring to live at the McLean’s estate. In her 1936 biography, Father Struck It Rich—the title coined from when her father exclaimed to her, “Daughter, I’ve struck it rich!”—Evalyn described a return to the great house:

"As I rolled under the porte-cochere in my green Duesenberg a few passers-by gathered on the sidewalk. One of the great plates of glass in the outer wall of that carriage shelter had been broken, possibly by a thrown rock… As I mounted the stone steps, I shivered. A stream of air poured out of all the reaches of the house. It was so cold, so much colder than the outdoors winter that it was almost visible, and it flowed swiftly. The house was as a cavern, a subterranean place in my past, and its deepest chill was lodged in my heart. This place had been my home."

Between 1936 and 1937, the U.S. government used the house for New Deal programs. Evalyn then tried to have the house rezoned for commercial use as either a hotel or apartment house, with shops on the first floor. The proposal met with stubborn opposition from neighbors, and the house was never rezoned.

In 1940, 2020 Massachusetts once again became the center of war work. Evalyn turned the house over for use as the headquarters of the District Chapter of the American Red Cross and the Washington Committee of the American League for Finnish War Orphans. The huge ballroom where the elite of Washington once danced was converted into a busy production office. The drawing room with its silk lined walls became executive offices. The music room was filled with plain wooden tables stacked with surgical dressings. The dining room’s walls were covered with shelves and filled to the ceiling with packages to be shipped overseas. The master bedroom became the public relations office, and the rest of the bedrooms were used as offices.

In 1942, Evalyn had to leave the Friendship estate where she had been living when the trustees of her husband’s estate sold the property to the federal government for dormitory housing for defense workers. It is now the McLean Gardens condominiums.

Upon leaving Friendship, Evalyn moved to a house at 3308 R Street, NW in Georgetown. The house had originally been called Mount Hope, but Evalyn renamed it Friendship as well. Even on a limited budget, Evalyn continued to entertain lavishly. She would hold weekly dinners where a hundred or more guests was common. Evening games usually included “pass the Hope Diamond."

Evalyn died in 1947 at the age of sixty from pneumonia at her Georgetown home. She insisted on wearing the Hope Diamond on her deathbed. After her death, her estate rented out the 2020 Massachusetts Avenue mansion until 1951, when it was sold to the Indonesian government for use as its embassy.