Franklin House and the Innkeeper's Daughter

In 1794, William O’Neale, a native of County Ulster, Ireland, moved from Chester County, Pennsylvania to open a stone quarry at Mount Vernon and one along the western boundary of the city to provide freestone for Washington’s new public buildings. It was grueling work, not only for the hired men and slaves, but also for O’Neale himself. The use of slave labor so frustrated O’Neale that he abandoned the quarries to stake his own claim in the new capital.

|

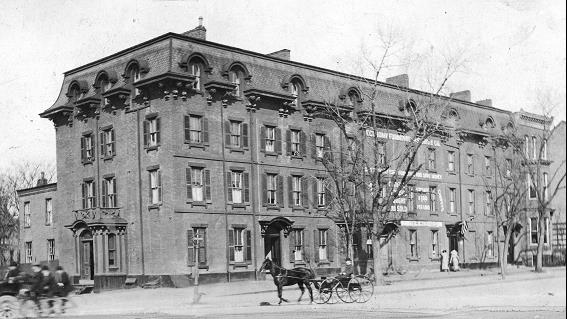

| Franklin House, circa 1913. The side of the MacFeely House at 2015 I

Street, now the Arts Club of Washington, can be seen to the far right. Historical Society of Washington, DC. |

In 1794, O’Neale built a wood-frame house at the corner of Twentieth and I Streets, just four blocks west of the White House, and made his living cutting and selling cord wood, coopering barrels and building stoves, as well as selling coal and feed. When he had saved enough money, he built a large brick house to the west of his house at Twenty-first and I Streets and put both his houses up for sale. But investors were not flocking to the new capital city as was hoped in the 1790s, and he was unable to sell either house. So in 1800, he turned the brick house into O’Neale’s Tavern, a boardinghouse and general store.

In 1813, O’Neale built an additional fifty foot wide house, containing twenty rooms, and was completely furnished. At this point, O’Neale’s establishment covered the western half of the block on the northern side of I Street between 21st and 22nd Streets and became widely known as Franklin House.

Although O’Neale was a successful hotelier, he was a poor businessman. In 1823, he sold the tavern and soon thereafter, it was bought by John Gadsby of Brighton, England. Gadsby also owned successful taverns in Baltimore and in Alexandria. Gadsby’s Tavern in Alexandria is once again open as a tavern and museum.

Franklin House was razed in 1914 and replaced with Penn Gardens, a pleasure palace with two movie theaters and a dance hall. Penn Gardens only lasted until 1927 when it was razed to build and apartment building on the site.

|

| Penn Gardens was built on the site of Franklin House in 1914. Historical Society of Washington, DC. |

William O’Neale is possibly best known as the father of Margaret O’Neale Timberlake Eaton. Born in 1799 and always known as “Peggy,” she was a celebrity at Franklin House. She was beautiful, well-educated, spoke French, could play the piano exceedingly well, and easily ingratiated herself with the guests at Franklin House.

At the age of fifteen, Peggy eloped with thirty-nine-year-old John Timberlake, who was a purser in the U.S. Navy. She had tried to elope once before with another gentleman, but her father caught her sneaking out a window and ordered her back inside the house.

|

| Peggy Eaton. Library of Congress |

The Timberlakes had become good friends with a twenty-eight-year-old widower, newly elected U.S. senator from Tennessee and close friend of Andrew Jackson, John Henry Eaton. When Timberlake was away on a four-year sea voyage on the USS Constitution, Margaret and John Eaton were often seen parading arm in arm, and talk began that the two were having an affair. Timberlake died of pulmonary disease in 1828 while away on the voyage. There were rumors that Timberlake had actually committed suicide because of despair over Peggy’s infidelity.

|

| John Henry Eaton. Library of Congress |

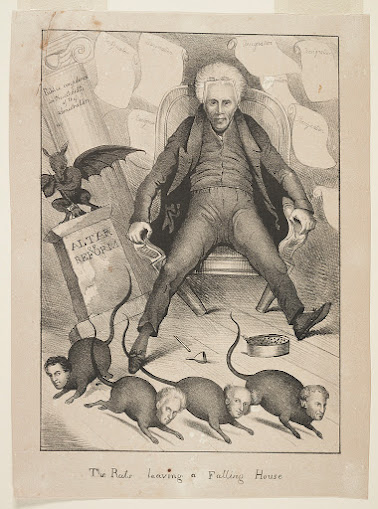

With the encouragement of President Andrew Jackson and throwing the customary one year period for a widow’s mourning aside, Peggy and John Eaton were married only months after Timberlake’s death, scandalizing official society, especially the women. Among one of the most scandalized was Vice President John C. Calhoun’s wife, Floride, who led other cabinet wives in an orchestrated attempt to snub and ostracize Peggy Eaton. Andrew Jackson’s niece, Emily Donelson, who had become the surrogate First Lady after the death of Rachel Jackson, also sided with the Calhoun faction. Martin Van Buren, a widower and the only unmarried member of the cabinet, sided with Jackson and John Eaton.

Hoping to quell the rumors, a sympathetic Jackson appointed Eaton as his secretary of war, which only exacerbated the situation, further enraging his opponents, especially the Calhouns. When he was advised against making the appointment because of Peggy’s reputation, Jackson barked, “Do you suppose that I have been sent here by the people to consult the ladies of Washington as to the proper persons to compose my cabinet?!”

The controversy finally resulted in the resignation of all but one member of Jackson’s cabinet over a period of a few weeks in the spring of 1831. They were replaced with Jackson’s trusted friends and advisors, which became known as the “Kitchen Cabinet” as they apparently did sometimes met in the White House kitchen. The situation became widely known as the Peggy Eaton Affair or the Petticoat Scandal. Jackson later appointed Eaton governor of Florida and then, in 1836, as minster to the Spanish court, where Peggy quickly became a favorite of Queen Christina.

|

| "The rats leaving a falling house." A satirical cartoon of Jackon's Petticoat Scandal caused by Peggy Eaton. Library of Congress. |

William O’Neale died at his Dupont Circle farm in 1837 at the age of eighty-six while Peggy was still in Spain was laid to rest in Holmead’s Cemetery, one of two public cemeteries that was once located at Florida Avenue and 19th Street, NW. When Rhoda O’Neale died in 1860 at the age of ninety, along with other properties the O’Neale’s owned around town, Peggy also inherited her father's farm in the Dupont Circle neighborhood.

Peggy Eaton’s scandalous life did not end with her effects on President Jackson’s cabinet. By the time John Eaton had died in 1856, Peggy had finally gained the respect of her socially elite associates in Washington, but her acceptance was to be short-lived. Only three years after Eaton’s death, the then fifty-nine-year-old Peggy married her granddaughter’s nineteen-year-old Italian dancing instructor, Antonio Gabriele Buchignani, who was working at Marini’s Dancing Academy. She was once again shunned by official society. Peggy did all that she could to get Antonio established in Washington, even trying to secure him a job at the Library of Congress, but to no avail.

|

| Peggy Eaton later in her life. Unknown artist. |

In 1866, Buchignani demanded that Peggy sign everything she owned over to him or he would leave her. In order to get him to stay, she signed over all her real estate, which consisted of nineteen houses and six square blocks that included the farm in Dupont Circle. Fortunately, she did not sign over the family home at Twentieth and I Streets. Buchignani then promptly sold the farm to the Hopkins brothers from Georgetown. The farmhouse stood at 1617 Connecticut Avenue until about 1895, when it was razed for a house for the widow of a gold miner, Ellen Mason White Colton, which still stands on the site today and has been converted to a storefront.

|

| The home of Peggy O'Neale at 20th and I Street NW where she lived with Antonio Buchignani after their marriage. Commission on Fine Arts. |

|

| Margaret O'Neale Easton. Between 1870 and 1879. Photo by Mathew Brady. Library of Congress. |

Peggy died in poverty in 1879 at the age of eighty-one at Lockiell House, a home for destitute women at 512 Ninth Street, NW. She had been living there for about a year. Those who knew her at the time said she was pleasant and kind, delighting int talking about the past,when she was young and held society agog. Shortly before her death, she looked out the window as light snow was falling and said: "What a beautiful world to leave." Peggy was buried in the capital’s Oak Hill Cemetery next to John Eaton.

|

| Lockiell House. Evening Star. |

In reference to the irony that Oak Hill is one of the city's most exclusive cemeteries and the criticisms Peggy Easton endured at the hands of Washington's elite, upon her death the New York Times editorialized:

Doubtless among the dead populating the terraces [of the cemetery] are

some of her assailants [from the Jackson years] and cordially as they

may have hated her, they are now her neighbors.

Antonio Buchignani died in New York City in 1891 at the age of fifty-seven.

|

| Grave of John Eaton and Peggy O’Neale Eaton, Oak Hill Cemetery, Washington, DC |

The 1936 movie The Gorgeous Hussy was based on the life of Peggy O’Neale and starred Lionel Barrymore as Andrew Jackson and Joan Crawford as Peggy.

|

| Site of Franklin House today. Google maps. |

Comments

Post a Comment